In this letter, Craig discusses his theory on why there are so few examples of William Shakespeare’s handwriting.

Author’s Note: An anonymous reader must have stumbled onto this page and they proceeded to email me to chastise and critique my alleged incorrigibility, gullibility, and naïveté. Despite what I wrote below and despite my attempts to more than insinuate at the beginning and at the end that I, too, have harbored significant doubts about the authorship of the plays and am open to any and all interpretation or investigation of the Poet, this person did not seem to be in on the joke. Though I do appreciate their commitment to their gospel and to its spread, even to the smallest of nooks and crannies of the internet, I promised I would revisit and deliver my true beliefs regarding the matter so there would not be any confusion. To be fair to the historical record, I will leave the below theory as I wrote it online, but I will deliver my personal theory in a follow-up soon.

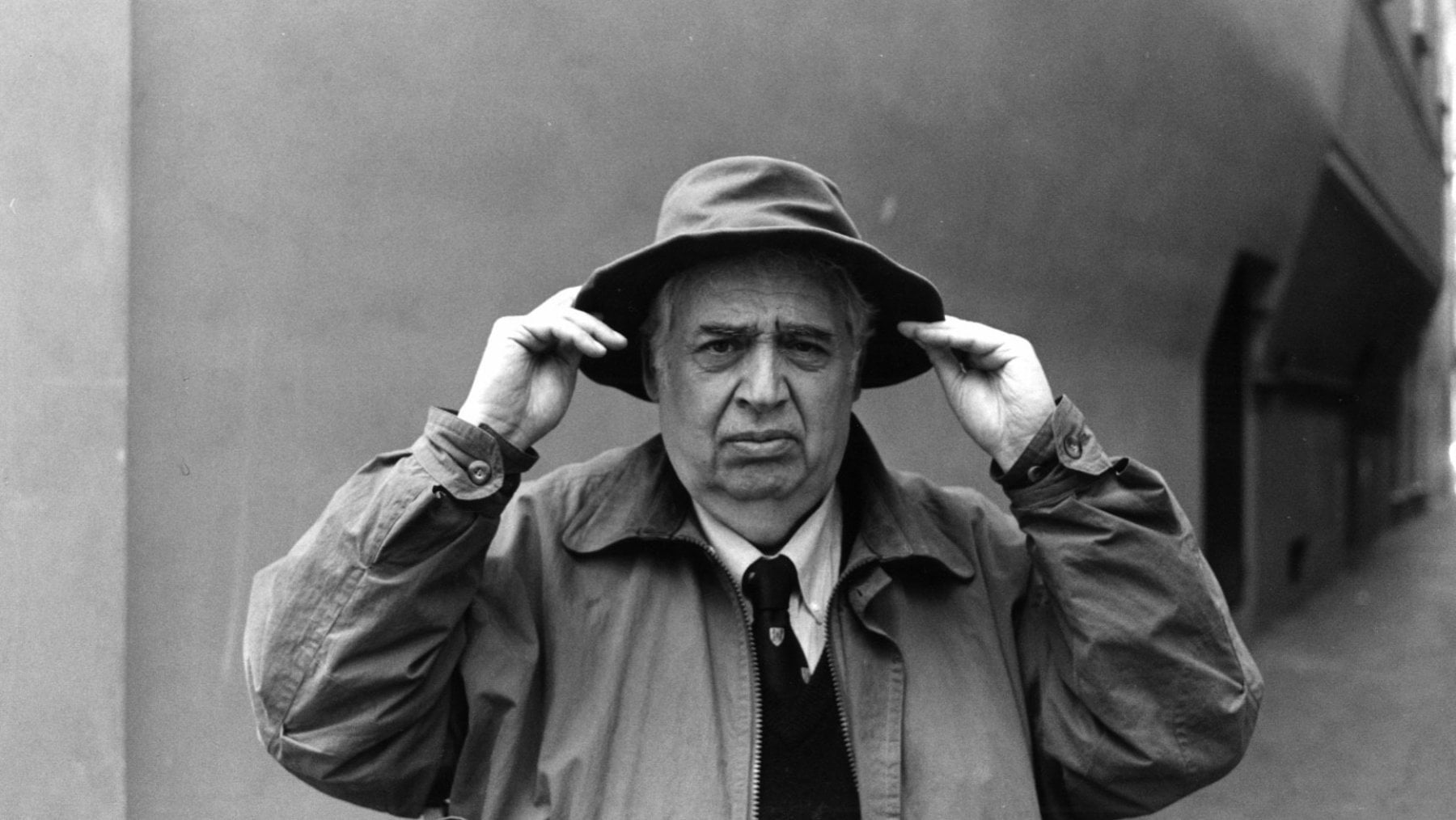

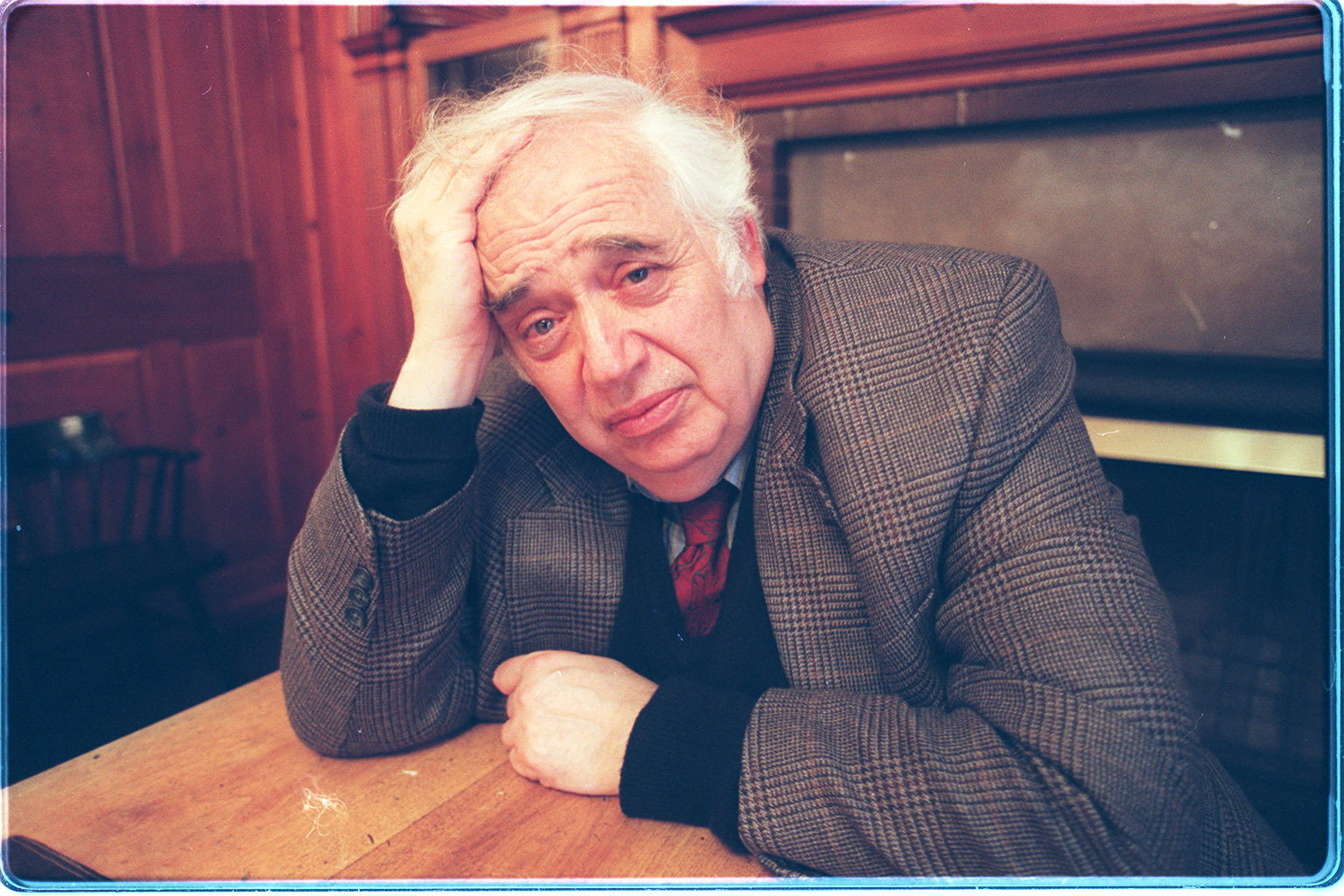

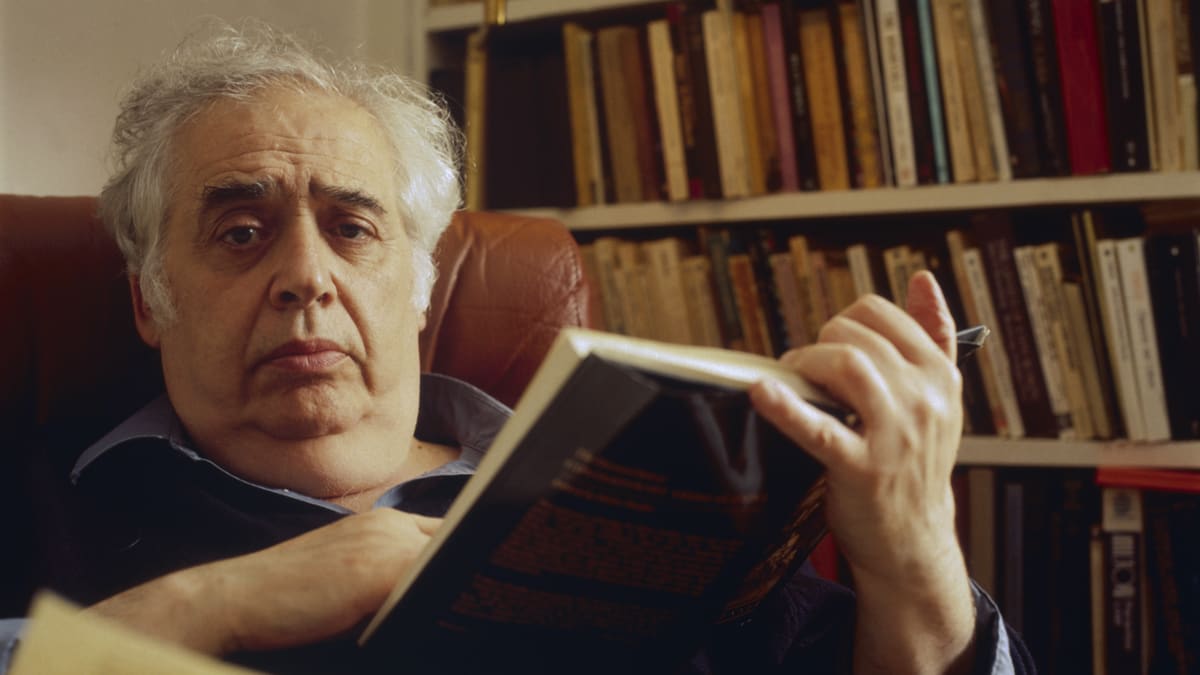

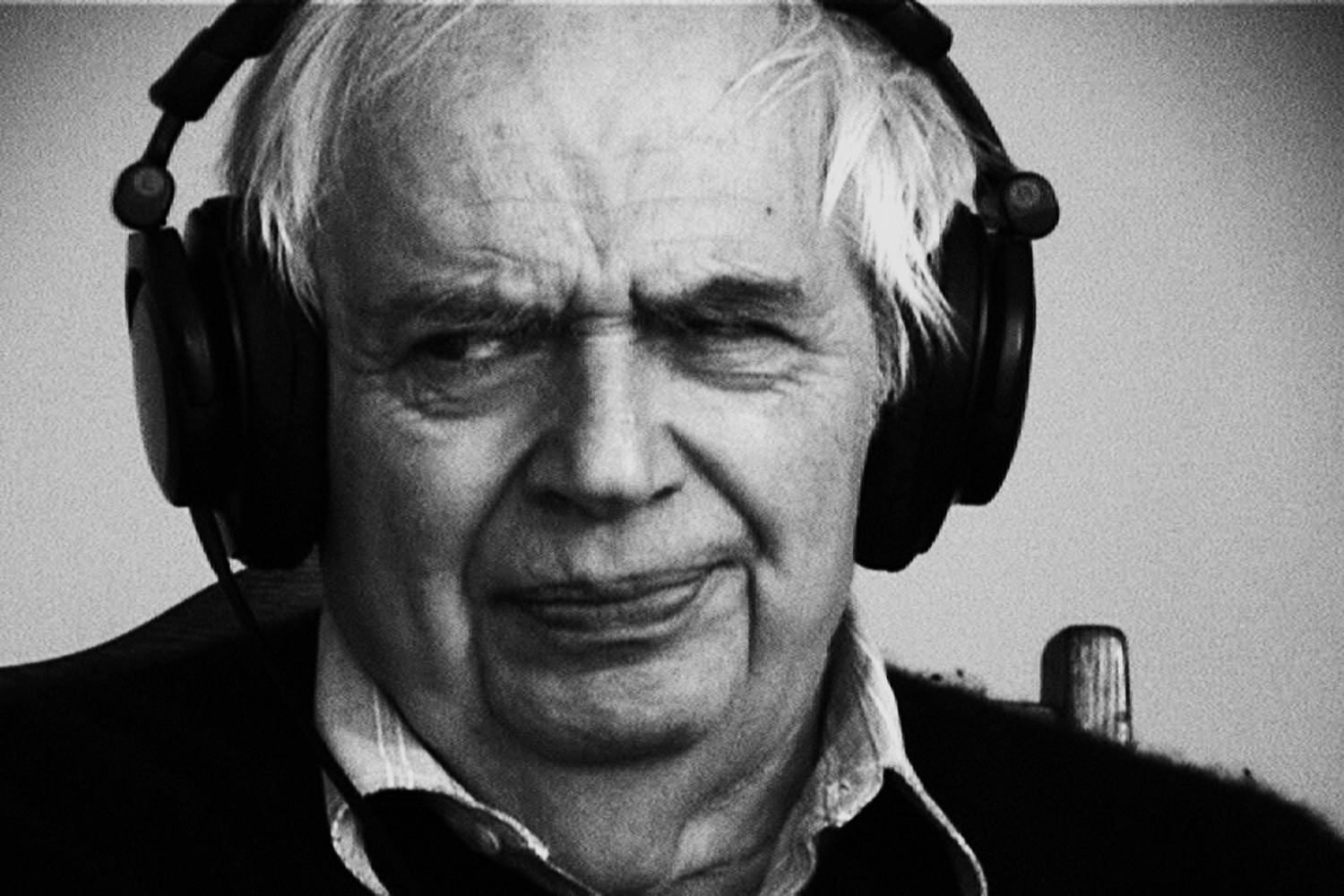

After Harold Bloom, the notorious American literary critic and Sterling Professor of Humanities at Yale University, passed away in the fall of 2019 I found myself experiencing an odd sense of loss. Not because I had ever met the man, nor because I had studied under anyone who had studied under him, nor because I whole-heartedly agreed with every argument or pronouncement he’d ever made about literature. I had not and did not in any of the mentioned.

My odd sense of loss came because, love him or hate him, and there is reasonable defense for both, Bloom was someone in a highly prominent position with a unique ability to get literature lovers talking. No, he is not destined to be the last of his kind, but to a certain person of my age and comparatively modest level of literature appreciation, I marveled at his pure passion for words and that passion inspired me to read and write with more of my own. Regardless of how anyone felt about his opinions on literature and all that surrounds it, there was no doubt about his unashamed love for it and, at a certain moment in my life, that passion for the enduring power of story spoke to my sensibilities.

If I’m being entirely honest, I was introduced to Professor Bloom largely through memes. Particularly after his infamous critique of David Foster Wallace, those of us old enough to have grown up in a time where independent booksellers could still exist and who grew up and hung out in the internet literati underground before the internet was locked down and taken over by modern corporate protectorates could reliably inside joke with each other using a simple .jpg of the many faces of Bloom.

But this isn’t about Harold Bloom. Sorry for the confusing lead. It’s just his passing that was part of the discussion that prompted the start of this letter.

I was talking to a friend recently and I mentioned I had long wanted to interview Harold Bloom if only just to hear him ruminate on some long lost favorite line buried deep in his photographic memory and to get a personal glimpse at his well-renowned recall and recitation abilities. To get my foot in the door for this imagined interview, I mentioned to my friend that I was going to try and entice Bloom with my theory on Shakespeare’s lack of handwriting. My friend asked me to go on and explain the theory and I brushed it off with, “it’s too long…” I recently thought about it again and decided, Well…your last few letters have taken a bit of a vague turn, maybe you should write that down and see if you can hold the topic?

Bloom was a noted lover of Shakespeare. Among other essays, he wrote full books discussing him, and, outside of religious scripture, he considered Shakespeare to be one of if not the center point of the Western Canon. As such, I thought my comparatively small theoretical observation would impress him. When I first came up with this little theory, I had never seen it written down or put forth anywhere else before, and I hoped this little theory would be enough to convince him to at least give me a small bit of his time.

Before I begin, I should make clear that I am no anthropologist, I am not a proper historian, and I am no Shakespearean scholar. So take everything I write below with far more than a dash of salt, a carefree attitude toward detailed historical research, a quizzical sense of I don’t know and likely never will, and a small wisp of wistful whatever. Some of this may take an additional explanation that I forget to include. Regardless, I’ve never seen it published anywhere, and even if it makes me look like an insane person, to me, it’s mostly an interesting little thought that maybe others who enjoy Shakespeare might find curious or spark another thread of thought all their own.

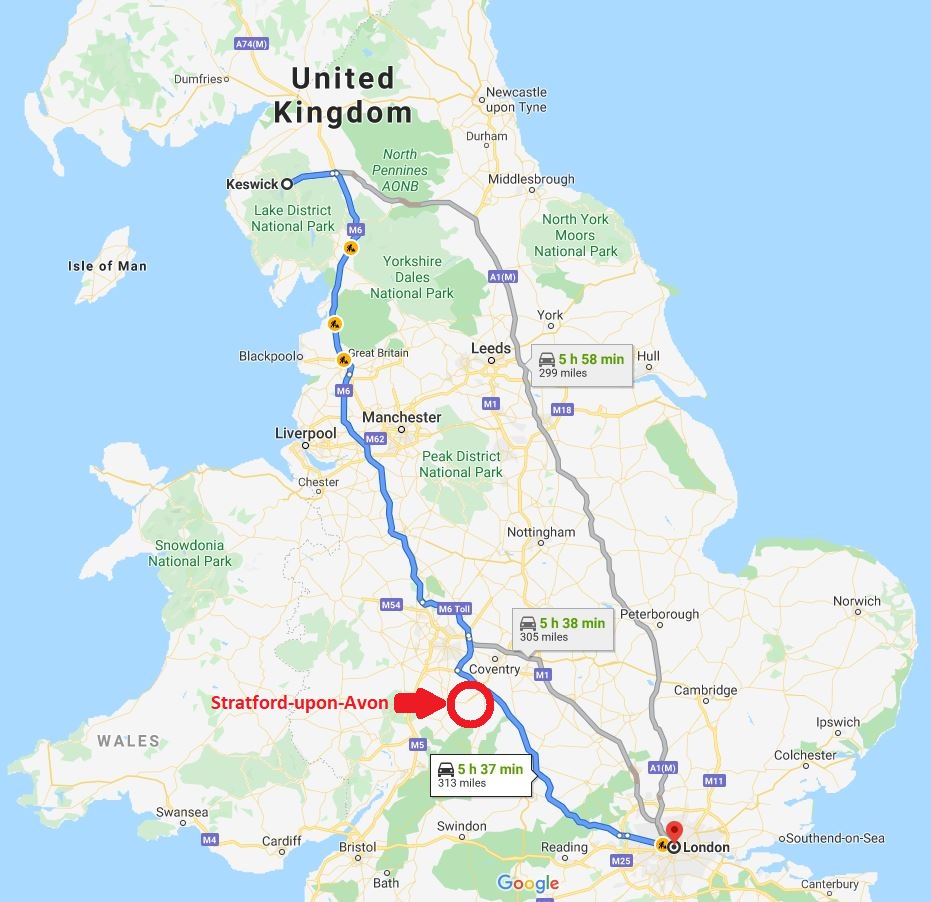

Anyway, this all first arose when I was looking into the Shakespeare authorship question. For those unaware, the Shakespeare authorship question is a long-running argument and debate that someone other than William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon wrote the works attributed to him. The belief that the Shakespeare of Stratford was a front to shield the identity of the real author or authors, who for some reason - usually social rank, state security, gender, or whatever other reason the person who refuses Shakespeare’s authorship chooses - did not want or could not accept public credit.

Despite all the research presented by the anti-Stratfordians, as they’re so-called, I always find myself eventually agreeing with their opponents and feel that the question against Shakespeare’s authorship most often boils down to either pure classism, some sort of modern pseudo-political academic scholasticism, and just plain jealousy.

Don’t get me wrong, there are astounding many intelligent individuals who do not believe either Shakespeare authored his work at all or, at the very least, it was not Shakespeare alone who was the sole author of his works and that it was a particular nom de plume or that he was mostly a “front”. So, anyone who’s reading this who has questioned the authorship of Shakespeare’s works, you’re in a company that includes such prominent historical figures as Walt Whitman, Mark Twain, Helen Keller, Henry James, Sigmund Freud, John Paul Stevens, Prince Philip - Duke of Edinburgh, Charlie Chaplin, and many more.

Also, to be clear, even if I have ultimately concluded that most arguments are classist and pseudo-political and jealous in nature (full disclosure: I have), that doesn’t mean I believe there are not some reasoned and reasonable questions risen by some of the anti-Stratfordians. In fact, this very theory was born out of one of those arguments I find most compelling and trying to find an answer for myself. And for further clarity, I’m not trying to make fun of anyone who doesn’t believe it nor am I one of those people who can not understand why someone would question such history.

I’ve even gone so far as to try to convince myself of the alternative and to find the most convincing answer to how and why it would have been done. What’s more, if I were to be convinced that Shakespeare was not the author of the plays, I do believe I also have the best theory for the Shakespeare authorship question and, let me tell you, it’s a helluva conspiracy theory if I do say so myself. It’s absolutely Pynchonian, mixed with some Umberto Eco and Roberto Bolano, stirred with some Kafka and Roth and a little Delillo, dashes of King’s Kennedy and Brown’s Da Vinci, bits and pieces of Condon’s Manchurian Candidate, finished off with spices of Clancy and Fleming thrown into the pot. It starts with the group at Wilton Circle, led by Mary Sidney Herbert, the Countess of Pembroke, who help fake Kit Marlowe’s death and we bring in some other real-life characters who would have most certainly requested help from the likes of Sir Francis Bacon and the eventual silencing of Ben Jonson for the greater good and the glory of Britain, yadda yadda yadda, etc., and then we add a few flavors until I had something resembling a plot filled with webs of intrigue and drama that could be described as properly Shakespearean in and of itself. The whole idea is very meta.

Maybe I’ll do another letter outlining that theory someday? I don’t know. Maybe. The amount of people interested in the drama surrounding historical literary figures decreases by the hour. In any case, for many, many additional reasons we can discuss at another time and over many drinks, I remain unconvinced. William Shakespeare is the Author.

That said, as I mentioned a little up above this line, there are a handful of things that have always driven me a little nuts about the whole issue and have always made me wonder, if only in the back of my head, maybe I was being a little too gullible? Naive? Too simple? Unsophisticated? I’ve never really minded being called a dupe, a sucker, an idiot, or a fool. As anyone knowledgeable in literary paradox should understand, playing the fool and the wisdom of the fool ain’t so bad. After all, it is when we can speak at our most freely. And that’s part of where this little theory comes from.

I see no realistic argumentative consequence in the denunciation of his education and social background, dating the works, hunting for and combing through the minute details of pseudonymous other’s lives, or trying to read the tea leaves in the scant remaining artistic impressions of the man. No, the things that bug me the most and drive my search for explanations are the little things, and one of these main points of contention is the lack of handwriting.

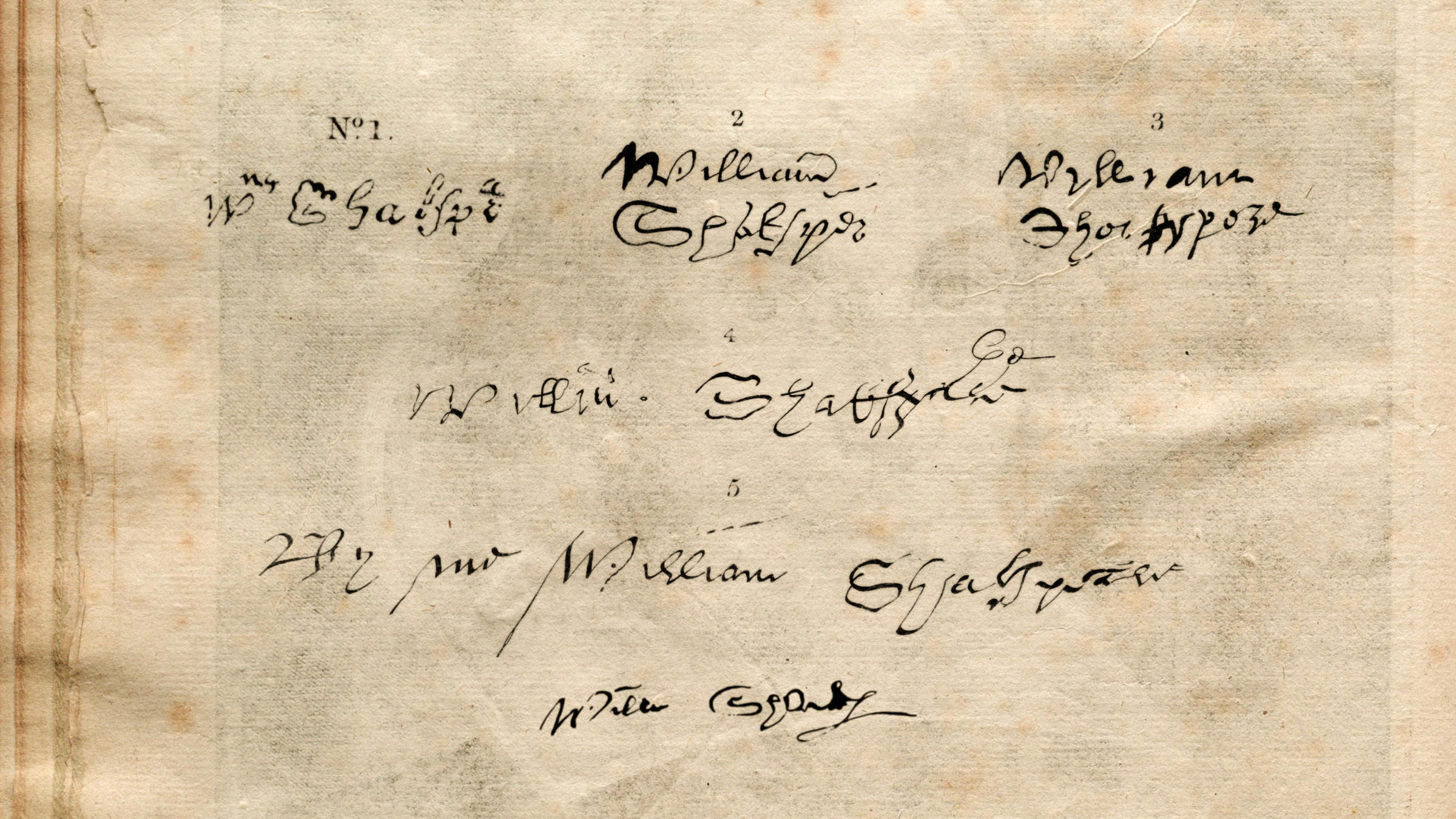

If you didn’t know, there are barely any examples. In fact, prior to the early 20th century, there were only 5 confirmed examples and they were all signatures. Since then, there has been a 6th signature confirmed and, although some dissenters remain, since the mid-20th Century it is now unequivocally believed by many scholars that 3 pages of the handwritten manuscript of the play, Sir Thomas More, are also in William Shakespeare’s handwriting. The play is believed to have been mainly written by two men named Anthony Munday and Henry Chettle. Just as it is in Hollywood today, it was relatively common for other playwrights of the Elizabethan and Jacobean era to collaborate, revise, and help edit scripts. There are, of course, other examples suspected to be in Shakespeare’s own hand. Some parts of the application for a family coat of arms is one, the body of his last will and testament, written in 3 parts and including the declining hand toward the end, is another.

Before I go further, I’ve heard all the counter-arguments to the lack of handwriting samples and the survival of manuscripts from the Elizabethan Period. I’m aware that recognition of historical value in something like a handwritten artifact is rarely found before the late eighteenth century. I’m aware that the realization that an old family archive possessing no practical value almost always results in destruction. I’m aware that for a writer with mass appeal like Shakespeare, working in a medium where performance was the main goal, the manuscript of one of his plays was of value only so long as they had a recognized practical value and that was the performance. In essence, once it was performed and put down in print, who cares? I’m aware that, though there is no manuscript of one of his own plays in his own hand that has ever been discovered, the same is true of the productions of the other playwrights who worked in the period from 1580 to 1642, and that no manuscript of any play has survived in the autograph of Kyd, Greene, Jonson, Chapman, Dekker, Heywood, Marston, Webster, Beaumont, Fletcher, or Ford – to name only some of the better known. I’m aware that no play by a professional playwright which was successful on the stage and which was printed before 1642 is known to have made it to today. I’m aware that, due to other factors like the pricing of paper or other necessary goods at the time, a particularly prolific author’s wastepaper would be much more valuable to the binder or the printer down the street or around the corner than it would to the author let alone any surviving family members. And, knowing Shakespeare could arguably be considered as a businessman first and the arguable greatest poet of all time second, this is not insignificant detail. Not being a scholar or historian myself, I can only agree that these and other explanations are correct and I’m aware that it’s these facts that make the following little theory entirely pointless and rendered moot before I even begin.

Still…I struggle…

I struggle with the idea that a man so gifted in Word would leave…barely a whisper from his hand.

I am initially convinced that he was more of an oratory writer, for lack of a better term, and that much of his work may have been worked out by vocalizing, rehearsing, blocking, and rote memorization. Outside of the “duh they were plays meant to be performed dummy” idea, there is some evidence to suggest that. The first in the form of Shakespeare’s own words in his plays. He wrote for and performed for the masses and commoner rather than the courtiers and he possesses a great understanding of how the everyday layperson of the time would have spoken. It’s filled with vulgarity and slang and retains a relatively natural speaking quality to it with patterns that are not traditionally what one would imagine if they were a writer obsessively concerned with every word they wrote down. Writing things down tends to make a person more deliberate and “high-minded”, and I encourage people to actually speak what they write. When a person reads their initial work aloud it helps clean things up and the voice makes glaringly clear what often sounds stilted and unnatural.

Additionally, there are the famous but admittedly perhaps apocryphal stories, that whenever he provided pages to the actors in his company there were never any mistakes or cross-outs on the pages. Further, John Heminges and Henry Condell, who edited the First Folio in 1623, wrote that Shakespeare’s “mind and hand went together, and what he thought he uttered with that easiness that we have scarce received from him a blot in his papers.” Ben Jonson, who was one of the most learned and towering literary figures of the time, knew Shakespeare and lamented that Shakespeare wrote too quickly and that he needed to slow down, while Shakespeare is said to have teased Jonson for being too slow due to thinking too much. Again, none of these stories could ever be verified but, for this particular discussion, they’re important to note.

And I can even be convinced that his talents for poésie simply had the je ne sais quoi touch of genius or were so unique or so far beyond normal that they would appear almost as if an idiot savant compared to even the hardest working wordsmith. As evidence, I might even point out it would take a supremely naturally talented 18-year-old poet to bed the 26-year-old Anne Hathaway and convince her he needed to go to London where he’d make his fame and fortune alone while she dutifully stayed home with the 3 kids. As any man will tell you, that bit of his biography, in itself, is nothing short of heroic and a feat no man, be he modern or antiquated, would ever argue is not a special gift from the Grace of God.

Still, I struggle.

I’ve found that People, with a capital ‘P’ and as a general whole, don’t change all that much. Despite it being known that, during his era, once something went to print most people cared little for the preceding endeavor, and even though it was practiced mostly among the wealthy who had the storage space and greater ability to care for documents, some people of the era did keep handwritten documents for their historical value. While I agree that due to an increase in the general welfare and free time devoted to leisure among the common individual, the average person has the ability to care far more about this today than at that point in history but since people do care about it today why would the historical average or middle-class person’s cares for it be nonexistent?

Before he achieved fame in London, Shakespeare’s family was far from unknown in the local community of Stratford. After he had achieved some level of fame and fortune to perhaps bring his family to upper-middle class, after he had acquired some wealth and property in both London and locally in Stratford-upon-Avon, there was not one family member who thought it particularly noteworthy and important to save a small memento of their most famous family member’s work that brought them not only that money but some level of fame? In London, none of the actors in his company or the poets amongst his peers or the printers amongst his friends paused for a moment and thought, “Hey…maybe we should hang on to a handwritten page or two? Maybe it’ll be worth something someday?” None of the wealthy patrons and benefactors slipped one of Shakespeare’s handwritten originals into a private library among their other documents for preservation?

Further, I ask myself why Shakespeare, the arguable greatest writer in the history of the English language and, arguably, the greatest writer in the history of the entire human race, of all time, a person whom no matter how oratory he wrote or intended for performance, someone as prolific and talented and practiced as he had to have been, left barely a trace of his original work? No matter if the performance was the thing, even the strongest photographic memory would be unable to keep all the edits and revisions and reworkings of line after line after line. He must have written a significant and substantial amount of words, right? Like…a lot of words. Pages and pages. Even if we accept that they flowed from his mind through his hand, they still had to have done so many, many times over. Am I crazy to ask in wonder how this person actually left so little written…anything? That he left so little physical evidence of his artform?

I don’t think so.

Writer’s are egotists. Supreme egotists. Just the idea that an idea should be writ down and refined and preserved and sent out into the world, and that this process could take weeks to months to years without any guarantee that it will ever be read or considered or looked at again requires an enormous level of textbook egotism. That someone not only talented at that process but who saw and achieved fame and notoriety and success in his own time would only serve to boost that egotism and narcissism. And no matter how humble the individual or no matter how much more important they valued the business side of their accomplishments, at some point, someone like William Shakespeare must - MUST - have had at least the passing thought, “Gee…I think I might be pretty good at this…”

And though he did not hold the almost mythical notoriety he holds today, he was recognized and eulogized by his contemporaries around him. William Basse wrote a poem suggesting Shakespeare should have been buried in Westminster Abbey next to Chaucer, Beaumont, and Spenser. Ben Jonson who, as we mentioned above was considered one of the most learned men of the time, who knew him and called him a friend, in his own eulogy, directly references Basse’s poem and emphasizes even greater sentiment. John Taylor, in The Praise of the Hemp-Seed, Leonard Digges, Hugh Holland, James Mabbe, Michael Drayton, Thomas Heywood, Sir William D’Avenant, Thomas Bancroft, John Warren, among other anonymous writers, make comment on Shakespeare’s unique qualities all within 25 years of his passing. Yet at no point did he or his family or his friends or the wealthy benefactors among the aristocratic class or those interested in the theatre seem to try and preserve at least one example from his pen? By the time of Ben Jonson’s death, approximately 20 years after Shakespeare, the general stigma of the theatre had already begun to lift and many considered the emerging plays as competitive examples of fine literature and playwrights in much higher regard. Yet none thought to pick up and hang on to not one extant illustration of his word captured from the aether by the antenna between his fingers?

Where is it? Where are the scribbles, the jots, the notes, the asides, the edits, the comments, the suggestions, the letters of correspondence?

Do we keep all of those things today? No, of course not. And there are even examples of other famous individuals specifically requesting all their work and papers be destroyed. Before he passed, Franz Kafka asked his brother to burn everything. As I mentioned in my previous letter, Abraham Lincoln was notorious for asking people to destroy his personal correspondence. But if you knew a famous writer would it not cross your mind? Or if it were your friend or family member and you were cleaning out a musty old attic, would you not think to hang on to maybe a couple of pieces? Or if you were a wealthy patron, would you not hesitate to clear more space in the archive or even actively seek out maybe just a little example of one of the more famous writers of your time?

I would. And, while I realize I am just one person with one opinion, I can confidently say I know more than a few who would consider the same. Would this really be so different back then?

So where is it?

It only leads to one additional question. What if those friends or family members or wealthy patrons would have saved something if they could have but they couldn’t? That it did not exist for them to save? But not that it did not exist for them to save because the writer that was Shakespeare did not write that which he is credited with. What if there’s an answer that leads us not down a suspicious conspiratorial road with its twists and turns and dramatic obstacles but toward a more common and pedestrian thoroughfare. When discussing Shakespeare, it’d certainly be ironic.

I promise, anyone with true knowledge of this issue who happens to find this little essay does not have to remind me that this theory is likely nonsense. And I don’t have to be reminded that we’ll never know.

But I would suggest that William Shakespeare primarily wrote in pencil. Plumbago, to be more specific. Wadd, if you’d prefer. Graphite, if you’d like to use the modern term. He did this, at least, for all his rough drafts and pre-performance work before transferring to expensive paper for final drafts. And to you austere Shakespeare scholars who have made it this far, before you laugh, allow me to explain. For that, we have to talk about his father.

John Shakespeare began his rise in Stratford-upon-Avon in his early twenties, presumably after he finished an apprenticeship as a glover. He quickly acquired property and mild status, first as the highly-desired position in any era, borough Ale-Taster. The Ale-Taster was tasked with ensuring innkeepers and publicans continue community goodness and wholesomeness in providing quality bread, ale, and beer. Within a couple of years his status increased as he was made a Constable, and over the following years continued to rise as an Affeeror, then a Burgess, and a Chamberlain. In that same approximately decade worth of time, he married into a local gentry family, the Ardens of Warwickshire, when he married Mary Arden, William’s mother. By the time he was in his mid-30’s and around the same time William Shakespeare was born, he became an Alderman. A mere few years after the young William’s birth, John was appointed High Bailiff, the present-day equivalent of the position of Mayor of Stratford-upon-Avon.

Again, in terms of local status, a quick rise during any time or place. But quick rises often lead to quick falls, and that’s not the end of John Shakespeare’s story.

When William Shakespeare was about 6 or 7 years old, John was accused of usury for lending a man named Walter Mussum the modern equivalent of approximately $50,000 with interest. Walter Mussum would die with barely half that amount of assets to his name. Within another year or two, John was prosecuted for illegally trading in wool when he was caught acquiring 8,400 pounds of the textile. As a glover, eliminating the pesky middleman this way would have been particularly opportunistic of the elder Shakespeare in his daily trade.

There were other rumors of impropriety and, by all accounts, with legal troubles and debts mounting, John seemingly withdraws from public life in Stratford around 1576-1577, when William is about 13 years old. From 1577-1586, he attends only one town council meeting in 1582, a couple of months before William marries Anne Hathaway. Consequently, in 1586, when William is 22, the once Mayor of Stratford-upon-Avon is stripped of his Aldermanic position. From there, John is largely gone from the historical record and both father and son fall into a combined “lost years”. They both resurface in 1592 when William is well enough known in London to be criticized in a local paper by another more elitist playwright, Robert Greene, with his famous “upstart Crow” comments while, at the same time that year, his father John’s name appears on a list of men who are not attending Church for fear of avoiding debts.

All of this is important to supplement my theory.

Sometime around William’s birth year (some say his birth year), in the Seathwaite hamlet of Borrowdale parish in Cumbria, England, part of the northern Lake District, local lore tells of a storm which uprooted a large ash tree (some versions say oak), where shepherds discovered a strange black substance clinging to its roots. It was initially called wadd, but was also termed white lead, black lead, bleiweiss, grafio piombino, bismuth, and plumbago. The locals quickly discovered this to be very useful for marking their sheep. Not soon after, its application for writing was realized and quickly spread. So quickly, in fact, that by the end of the 16th Century, what we now call graphite was well known throughout Europe for its superior line-making qualities, its erasability using bread as an eraser, and the ability to re-draw on top of it with ink, which is not possible with lead or charcoal.

This particular graphite discovery was so significant, in fact, to this day there is still nowhere in the world with such large quantities of graphite with the purity and unique qualities of that which was first discovered and mined at Borrowdale near Shakespeare’s birth year. In later years, as it became significant in minting coins and useful in lubricating cannonballs, the Crown would take control of the mine and the price of this graphite on the market would skyrocket into the thousands of pounds. For a time, the value would surpass even gold.

Again, I’m no historian or proper Shakespearean scholar but, does this not sound like exactly the sort of thing that let’s say the minorly unscrupulous businessman named John Shakespeare, who was a glover by trade and who was prosecuted for illegally dealing in wool, would know about and maybe even be in the business of trading as well?

Now, you may be quick to point out that there is no official record of graphite writing instruments wrapped in wood until the 17th century and you’d be correct. The pencil, as we know it today, Shakespeare may not have ever known. However, there are others who would make us consider it possible. As early as 1565, there is a notable description in a book on fossils by the Swiss physician, naturalist, bibliographer, and philologist, named Conrad Gesner. Gesner describes a writing instrument, “The stylus shown below is made for writing, from a sort of lead (which I have heard the English call antimony), shaved to a point and inserted into a wooden handle.”

Regardless of the wood pencil being known to William Shakespeare or not, we do know that the first writing utensils utilizing this newfound substance were wrapped with wax or string to help keep the hand clean. What’s more, a quick visit to the Keswick Pencil Museum will tell you, there is evidence that Flemish traders were supplying the Michelangelo School of Art in Italy with Cumberland graphite as early as 1580. Proof that the reputation of the mine for quality wadd/plumbago/graphite spread quickly across Europe. At the very least, by 1610, within Shakespeare’s lifetime, the knowledge of the “black lead” as a writing instrument was well known enough it was being sold regularly in the streets of London and wrapped in paper, string, and twigs. It was commented on by another writer of the day as follows:

“note them with a pensil of black lead for you may rub out againe when you will with the crums of new wheate bred…”

My contention is Shakespeare was, in the 5 Stages of Technology Adoption, was likely an Innovator or, at the latest, an Early Adopter. In London today, he’d likely even be called a Lighthouse Customer.

Here’s a picture of what I’m referencing:

Does this history prove my theory? No, of course not. All this does is ask more unanswerable questions, but asking questions in this direction and considering the possibilities and likelies based on this accumulated history could lead to more coherence in the unanswerables.

In his earliest years, William lived in relative safety, secure in middle-class respectability in the country town of Stratford. An outcome any parent would desire for their children and, I have to assume, that John Shakespeare would feel no different. After this relatively pleasant early life, during his most formative pre-teen and teenage years, his father makes a consequential set of decisions where, essentially, his father loses much if not most of what he had built. Is it unreasonable to wonder just how much the sudden change in class and station would affect the young William Shakespeare’s life?

These decisions, while certainly against the laws of the time, wouldn’t necessarily be difficult to see how someone could understand an alternative perspective and sympathize with the underlying reasons and explanations. Though we haven’t discussed it in detail, it wouldn’t be difficult to see how a closet Catholic might feel about giving his government its “due” after a sweeping shift to Protestantism in 1558 upon the ascension of Elizabeth I. How someone, perhaps a teenage and young adult son, would see firsthand how severe and devastating a loss of personal financial resources, local reputation, and political and religious attitudes could/would affect his father and his family? Maybe that would affect how he would later treat his profession and how he would cater to business first and art second? Maybe he would cherish the paper and sheep’s wadd as his only affordable creative outlet and as he grew he would continue to prefer the “erasable” option to practice over and over and over? That the performance, where the business and the money rolled in, would be the only valuable appraisal of his practice personal reputation? And he would continue to preserve and save as much of the almost equally valuable paper as he could and, no matter how supremely talented he was at his art, he would focus the most important lessons to his heirs not on his artistic successes but rather the safety and security his business successes brought him, by any means and talents necessary?

While some suggest William’s treatment of the father/offspring relationships in his plays is one of ill, I would disagree and argue that his depiction of some of the fathers at their worst was a reflection of things he’d read and heard and heightened for dramatic effect rather than his own relationship with his father or his relationship with his own children. I would further argue that it’s his seemingly most personal plays where he appears to be at his most self-reflective that we see more truth in his personal family relationships. In those works, I do not get the sense that William was ashamed of his father. It’s widely believed he was the one that finally pushed his father’s application for a coat-of-arms through when he achieved enough fame on the stage in London. And, despite how much time away from Stratford he spent, at no point does his own family and children seem to hold any significant ill toward him. In fact, late in life, his son-in-law frequently makes the business trips to and from London with him and helps to manage his affairs.

I’m digressing. If I continue reviewing all father characters and themes in Shakespeare’s works this will run on much farther than I want to take it and I’m sure farther than anyone wants to read it.

I’ll say for the last time, I know we’ll never really know what Shakespeare used in his creative process and I’m not going to be the one to find out with any certainty. I’ll finish with only a few more unanswerable questions.

Maybe the answer is the most devastating of all? That time cares not for our remnants. That neither our manuscript nor monument should matter to Men. That it is silly for us to believe that if we could imitate the way a hand drew another mind’s thoughts or see the grammar choices in a little note tossed into a margin we could glean insight into how genius works and we would be imparted or somehow imbued some of that genius into ourselves. That we are but fools to believe that a dip of our hand into a river to drink would reveal some mysterious heretofore unknown secret and allow us to understand the essence of the wellspring source upstream from whence it came and, in our ignorance, we would fail to recognize and forget to notice the water’s cool, refreshing, life-sustaining taste held in our hand. Which is what it’s there for. That we should worry not because the greatest gift we can offer ourselves and our posterity is a life well-lived in service to those closest to us. That it’s a life well lived that keeps the world turning and the stage well lit and, as the rains fill our gardens and our fields and help bloom new flowers and new crops grow with each journey through the seasons, new stories brought by new player’s lives refreshes and replenishes our imaginations for the next generation of storytellers to come. That it’s the joy received from a friend, a family member, or an audience that fills our sails and is our soul’s great reward.

Maybe he said as much?

…

Sonnet 16

But wherefore do not you a mightier way

Make war upon this bloody tyrant, time,

And fortify yourself in your decay

With means more blessèd than my barren rhyme?

Now stand you on the top of happy hours,

And many maiden gardens, yet unset,

With virtuous wish would bear your living flowers,

Much liker than your painted counterfeit.

So should the lines of life that life repair

Which this time’s pencil or my pupil pen

Neither in inward worth nor outward fair

Can make you live yourself in eyes of men.

To give away yourself keeps yourself still,

And you must live, drawn by your own sweet skill.

Hamlet - Act 1, Scene 5

O all you host of heaven! O earth! What else?

And shall I couple hell? Oh, fie! Hold, hold, my heart,

And you, my sinews, grow not instant old,

But bear me stiffly up. Remember thee!

Ay, thou poor ghost, whiles memory holds a seat

In this distracted globe. Remember thee!

Yea, from the table of my memory

I’ll wipe away all trivial fond records,

All saws of books, all forms, all pressures past

That youth and observation copied there,

And thy commandment all alone shall live

Within the book and volume of my brain,

Unmixed with baser matter. Yes, by heaven!

O most pernicious woman!

O villain, villain, smiling, damnèd villain!

My tables!—Meet it is I set it down

That one may smile, and smile, and be a villain.

At least I’m sure it may be so in Denmark.

So, Uncle, there you are. Now to my word.

It is “Adieu, adieu. Remember me.”

I have sworn ‘t.

As You Like It - Act 2, Scene 7

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms;

And then the whining school-boy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths, and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lin’d,

With eyes severe and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slipper’d pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side;

His youthful hose, well sav’d, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank; and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion;

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

Macbeth - Act 5, Scene 5

She should have died hereafter.

There would have been a time for such a word.

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day

To the last syllable of recorded time,

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

The Tempest - Act 4, Scene 1

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air:

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.

The Tempest - Act 5, Epilogue

Now my charms are all o’erthrown,

And what strength I have’s mine own,

Which is most faint. Now ‘tis true

I must be here confined by you

Or sent to Naples. Let me not,

Since I have my dukedom got,

And pardoned the deceiver, dwell

In this bare island by your spell;

But release me from my bands

With the help of your good hands.

Gentle breath of yours my sails

Must fill, or else my project fails,

Which was to please. Now I want

Spirits to enforce, art to enchant;

And my ending is despair

Unless I be relieved by prayer,

Which pierces so, that it assaults

Mercy itself, and frees all faults.

As you from crimes would pardoned be,

Let your indulgence set me free.